A_CAMADO(A) (BEDRRIDEN).

My great-grandfather went blind. It was not a gradual process, but sudden. He did not follow medical advice after having cataract surgery. He was blinded because he insisted on watering the garden. That is what I was told.

This work is an imaginary exercise exploring identity and self-definition: if I were at the foot of his bed, how would I self-describe when I first introduced myself to my great-grandfather, who became blind at the end of his life?

”I am a Latino woman in my late 40s, with shoulder length brown hair and average height.” - I would say. But, only when I became a Brazilian living in North America I began to auto-describe myself as a person of color. In the Brazilian social context, I am a white woman. To omit such a description would be to fail to recognize that generations of my family enjoyed certain privileges in our home country because of this lighter layer of skin.

“Being white consists of being the owner of symbolic and material racial privileges.”

Branquitude Estudos sobre a identidade Branca no Brasil - Cardoso, (2017).

Self description:

Access and social inclusion of people with visual disabilities is finally being embraced in our social interactions, especially virtually, and invites that a physical description of the individual be offered.

By self-describing oneself, an individual exercises an act of self-definition and identity, and therefore such a description becomes a political and social act.

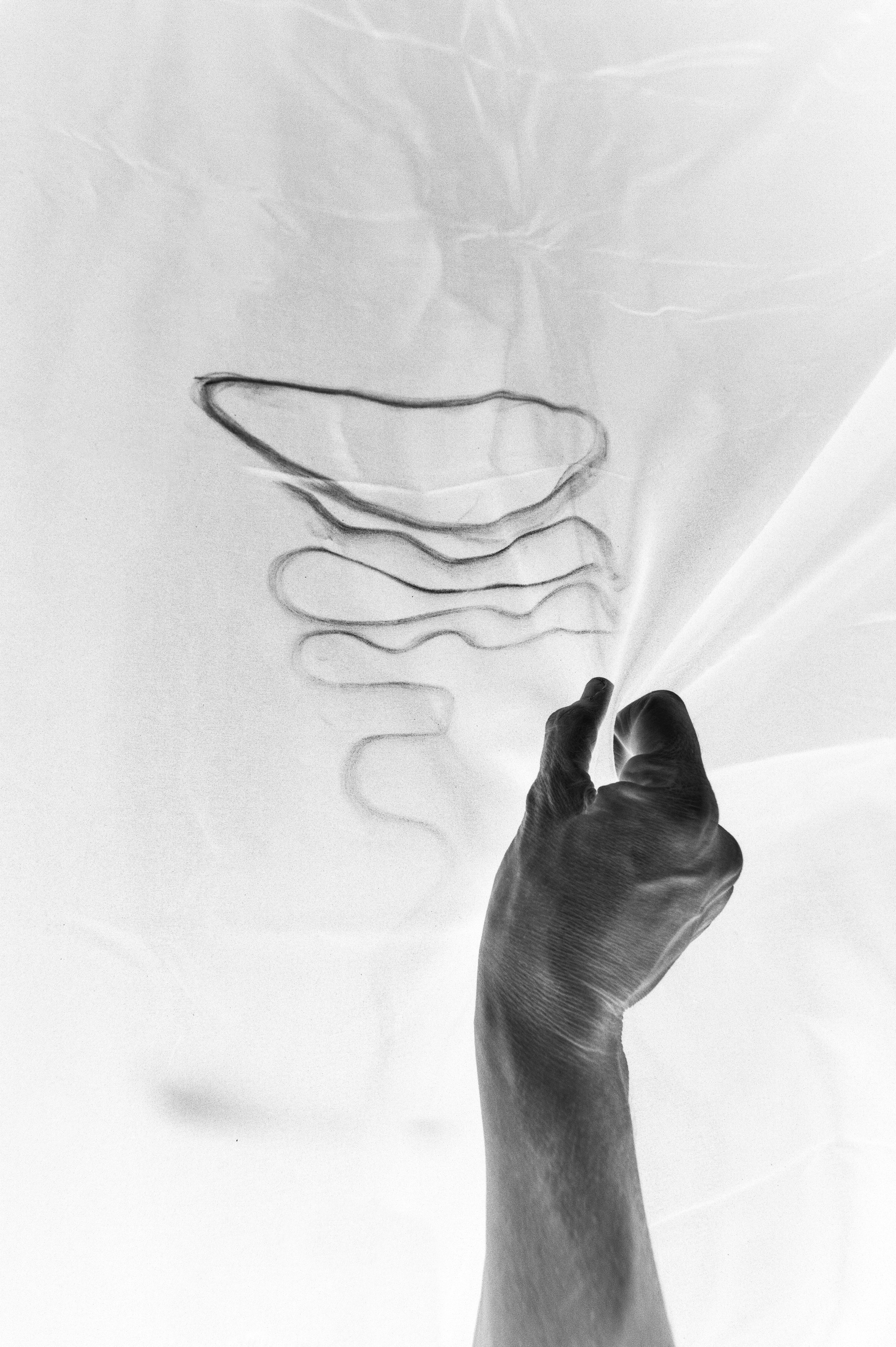

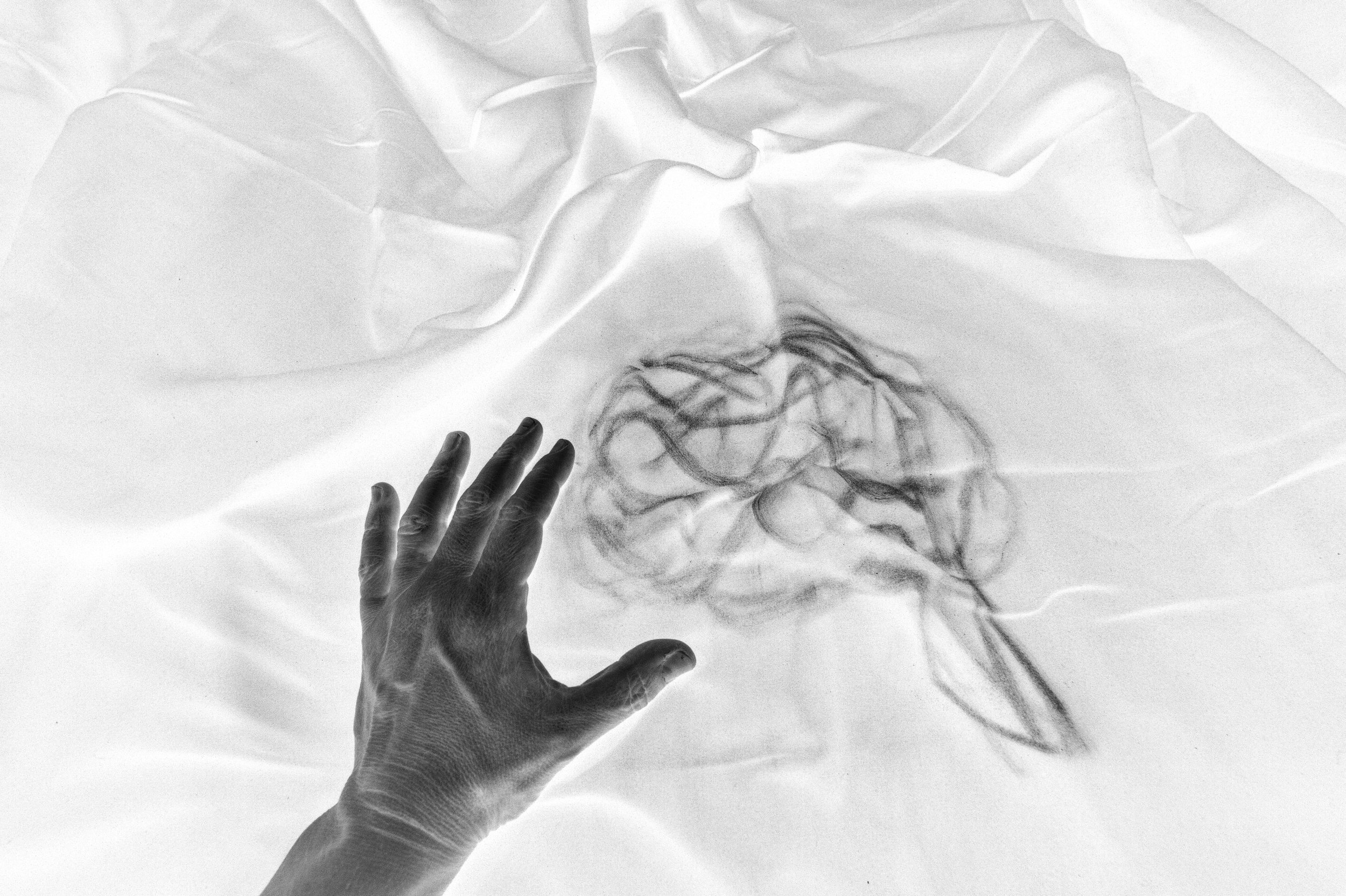

My skin layer is reversed in these images, as well as my roles in the society in which I find myself. My hands extended from the edge of the bed represent an existence on the margins, and the dichotomy of this alternation between spaces. The unacceptable white priviledge carried in the north and south, east and west on Brazilian soil, finally unravels when transported across hemispheres. White identity and white privilege are not applicable in North America. Here, we are not white people, we are people of color.

Being a Latina gives me access to the rich belonging, identity and community that exists within latinidad; And at the same time, makes me a witness of the social disparity that is a frequent part of the Latino experience operating as human capital in the global north.

In hospitals, nursing homes, assisted living facilities for the elderly, as well as most private nurses and assistants, large numbers of caregivers in the global north are black and brown immigrants from the global south.

Until the end of his life, my great-grandfather José Vieira Gomes dos Santos Arcoverde had a caregiver - just like my grandmother in the last days of her life, and my mother in her old age. While bedridden, care, help and support were given to these members of my family from black hands.

I visually explore the ambivalence of my identity - a woman of color in North America, and a white woman in my own home country; I also represent a lineage of the privileged white elite in Brazil and elsewhere, that benefit from structures of systemic racial inequality in institutions, including health services.

I insert phrases taken from Saramago not only to represent the sudden loss of sight that befell my great-grandfather, but mainly to expose the distorted lens of whiteness that emerges every time family histories are told without acknowledging the systemic racial inequalities that generations of my ancestors benefited from.

By using embossed labels, I add a textual-tactile element as if I could imagine a perceiving without looking, a knowing without seeing - but that of touch and feeling. I question myself about the use of not-seeing as a metaphor for not-knowing, so permissively present in ablelist narratives - a frequent attribution to this work by Saramago. I reject the use of blindness as metaphor and resignify the “white-evil” that beffals his characters as a metaphor for “white gaze” supremacy that sustains erasure and exclusion in white-centric social spaces still insisting to deny that in such spaces “a whiteness covers everything”.

At the foot of the bed, each of my gestures is an attempt to touch my ancestry at the heart of our coloniaty in order to transmute it. Do we know who we are? Do we know who we were? I whisper: “Know thyself” and, be no longer what you once were.

“In his own whiteness, the blind man may come to doubt”

- Saramago, Ensaio sobre a cegueira, (1995)

References:

Benjamin, Ruha. Viral Justice: How We Grow the World We Want, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691222899

Menakem, R. My grandmother's hands : racialized trauma and the pathway to mending our hearts and bodies. .

Müller Tânia Mara, & Cardoso Lourenço. (2017). Branquitude Estudos sobre a identidade Branca no Brasil. Appris Editora.

Saramago José. (1995). Ensaio sobre a Cegueira. Harcourt, Inc.

AMERI_CANA

A_CAMADO(A) is part of a series of works called AMERI_CANA where I explore spaces between myth and reality, tales and memory, history and fables. In passed down stories, the unfinished tracings of the diaspora of multiple generations leaves gaps that welcome the imagination and delusional fantasies of identity, while historical documents eliminate any minimization of our ancestral colonial roles - from the Brazilian northeast to the American northeast - From sugarcane to a dream of America.

#ameri_cana #decolonizing #familyhistory #ancestralhealing #ancestralidade #genealogia #latinidade #identidade #workinprogress #photography #archives #migration #diaspora #america #cana #canadeaçucar #plantations #sugarcane